Context

Studies show that when individuals are asked to reflect on what matters most in life, their personal health and the health of their loved ones consistently emerges as one of the top priorities. The absence of good health not only diminishes an individual’s quality of life, but also impairs their capacity to partake in social activities and interactions and contribute to the workforce. Additionally, the repercussions of poor health extend beyond the individual level, impacting our friends, families, communities, as well as the health system and broader economy.

The COVID-19 pandemic had an unprecedented and profound impact on health in Australia. It put health at the forefront of decision making, and showed us that without good health, we cannot function as individuals or as a society. It also caused a dramatic and permanent shift in how, when, and where healthcare is delivered, and how remarkable things can be achieved when governments, healthcare professionals, and communities work together.

Importantly, the pandemic exposed significant shortcomings in our system that were present well before the pandemic. Australia is now facing major health workforce shortages, increased demand, increased costs of providing high-quality healthcare, the aftermath of COVID-19, including delayed care and long COVID, and rising costs of providing healthcare. The AMA’s Vision for Australia’s Health 2024–2027 represents a blueprint for addressing these challenges and building a sustainable healthcare system.

Australia is facing an increasing burden of disease

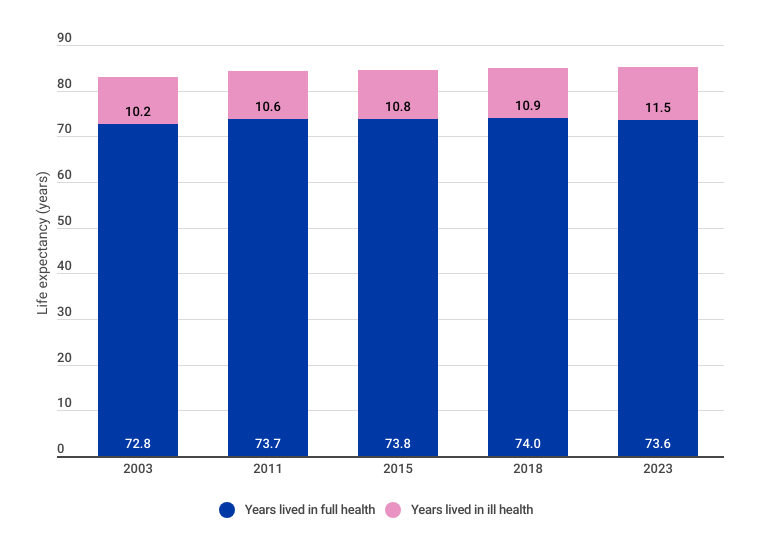

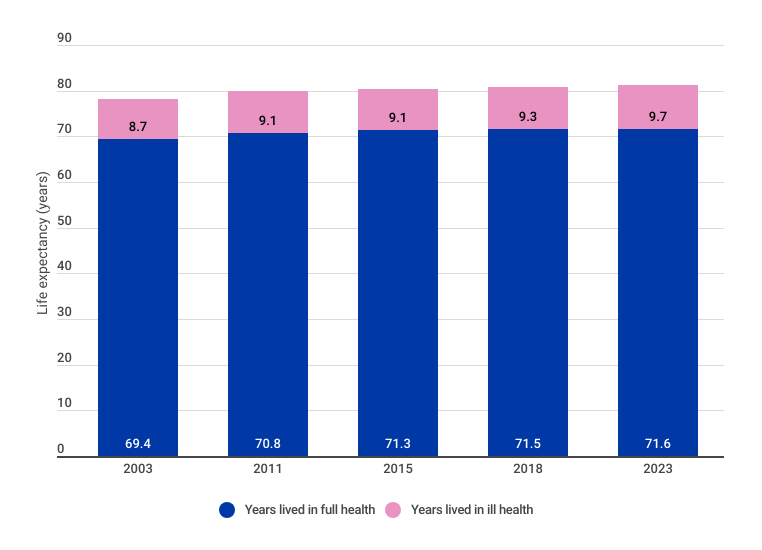

In 2023, Australians lost 5.6 million years of healthy life due to living with illness or injury and dying prematurely.1 In 2023, Australians were estimated to live about 11.5 years (females) and 9.7 years (males) in poor health. This is about 13.5 per cent (females) and 11.9 per cent (males) of their lives, with the number of years lived in ill health increasing over time for both males and females (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The five disease groups that caused the most burden of disease in 2023 were cancer, mental health conditions and substance use disorders, musculoskeletal conditions, cardiovascular diseases and neurological conditions ― chronic and long-lasting conditions that together account for about two-thirds (64 per cent) of the total disease burden. Almost half of all Australians now live with at least one chronic disease, and one in five live with two or more chronic conditions.2

Australia’s private health system is also facing challenges. Pre-COVID, from June 2015 to June 2020, private health insurance membership fell for 20 successive quarters. Like the broader population, the age of the insured population is increasing; while Australians aged 75 and older have increased their insurance membership by 3 per cent, 25-34 year olds have dropped a full 6 per cent, between 2015 and 2018. This creates a cycle of increasing insurance premiums as insurers seek to deal with the increased cost of care per policy holder. It creates a health system out of balance for everyone, with a dwindling funding pool2.

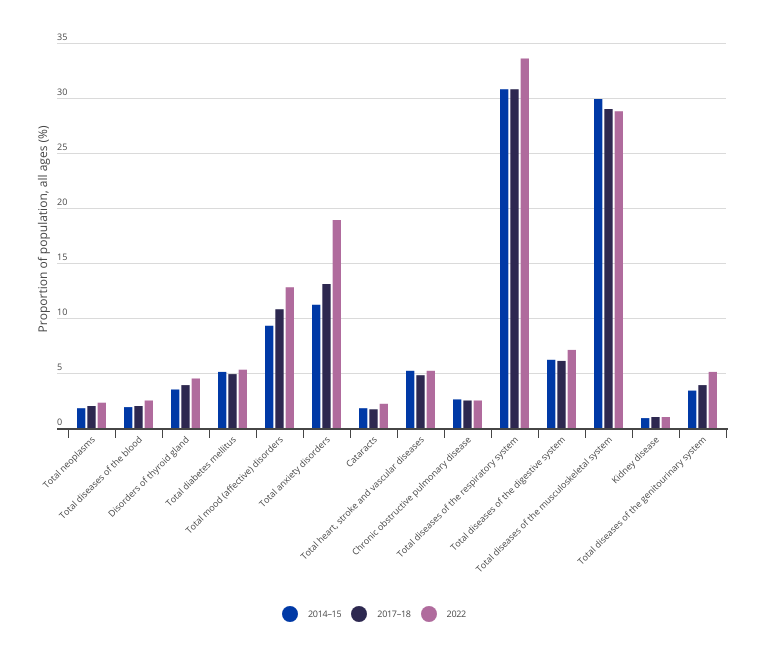

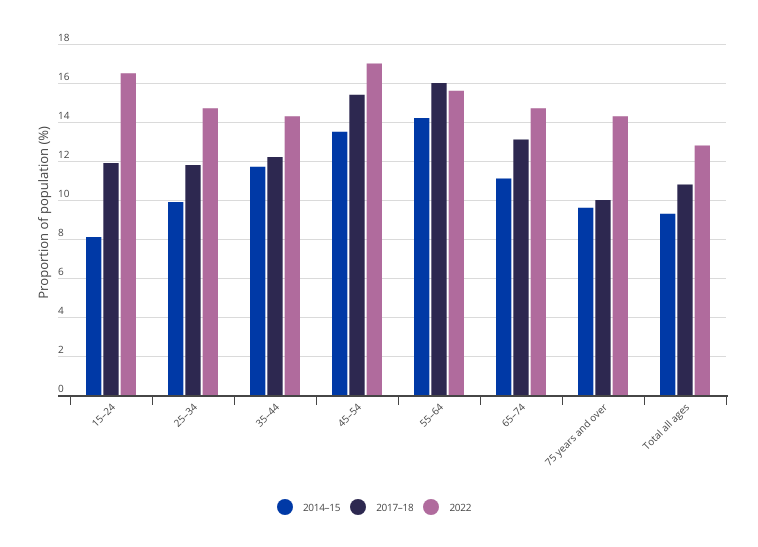

The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics National Health Survey demonstrates that for most conditions the burden of disease has been increasing over time and will likely continue to grow if not addressed (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Australian female life expectancy and health, 2003 to 20233

Figure 2: Australian male life expectancy and health, 2003 to 20234

Figure 3: Proportion of the total Australian population living with disease by disease group, 2014–15, 2017–18, 20225

This burden of disease is experienced unevenly in Australia, with many groups experiencing health inequities and challenges that result in a disproportionately higher burden of disease. It is important to recognise individuals may belong to many of these groups simultaneously, and this intersectionality compounds the challenges they face, underscoring the need for tailored, multifaceted approaches to address health inequities. These groups include:

Older Australians

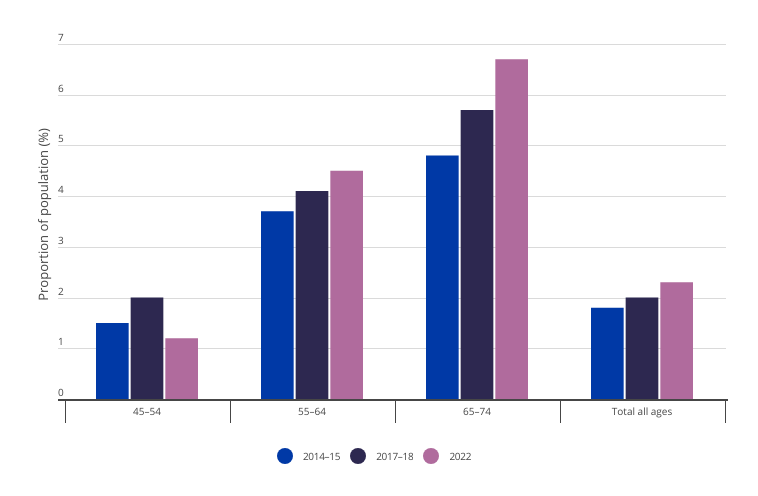

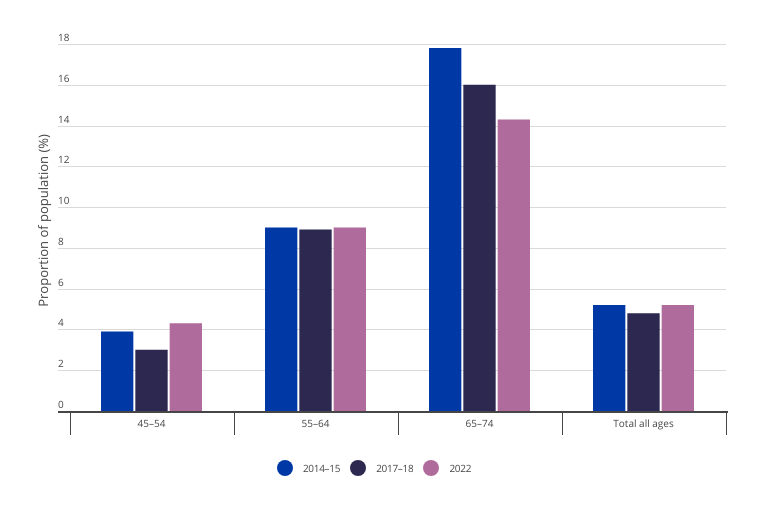

It is well known that the Australian population is ageing and the burden of disease for many conditions increases with age. For example, Figure 4 demonstrates the 45–54-year-old cohort has a below average rate of people living with neoplasms. In the next age cohort, 55–64, the share is about double the average, and the subsequent age cohort (65–74) is about three times the average. As the Australian population continues to age over the next two decades and this burden of disease continues to grow, the impact on healthcare costs, as well as broader economic output, will be substantial. Governments will therefore need to look at ways to reduce this disease burden in older cohorts, and where this is unachievable, offer treatment options which maximise quality of life. There are many conditions however that disproportionately impact younger Australians, for example mood disorders, which are more likely to impact younger Australians (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Proportion of the Australian population with neoplasms by age group, 2014–15, 2017–18, 20226

Figure 5: Proportion of the Australian population with mood (affective) disorders by age group, 2014–15, 2017–18, 20227

Lower socioeconomic groups

One of the most well-documented health disparities exists among lower socioeconomic groups. Australians in lower socioeconomic groups have less access to healthcare facilities and preventive healthcare services as well as determinants of health, such as education, healthy foods, and safe housing. As a result, these groups are at greater risk of poor health, have higher rates of illness, disability, and death, and have lower life expectancies compared to people in higher socioeconomic groups.8

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a right to access appropriate, affordable, and culturally safe healthcare wherever they are in Australia, and in whichever setting they choose. Providing culturally safe healthcare requires truth telling, redressing the historical impacts of colonisation — which continue to persist — and eliminating the institutionalised racism that currently exists in the Australian health system.9 This will be achieved by ensuring self-determination for decisions that impact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their health, and supporting and growing the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience some of the most pronounced health disparities, with the rate of disease burden more than double (2.3 times) that of non-Indigenous Australians and a gap in life expectancy of 8.1 years (females) and 8.8 years (males).10 The key contributors to disease burden include mental and substance use disorders, injuries, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and musculoskeletal conditions. It is estimated 35 per cent of this health gap can be explained by social determinants (e.g. employment, income, education, housing) and 30 per cent can be explained by selected health risk factors (e.g. smoking, poor diet).11 The rest of the gap is likely due to more complex factors, such as access to affordable and culturally safe healthcare, connection to Country and language, and the impact of colonialism, racism, and discrimination.12

Culturally and linguistically diverse groups

Australia is one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse countries in the world, with three in 10 people living in Australia born overseas.13 Research demonstrates many people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds face greater challenges navigating Australia’s healthcare system, including language barriers, lower health literacy, cultural differences, socioeconomic disadvantage, and discrimination.14 The diversity in cultures, languages, religions, social values, and migration trajectories makes it difficult to measure the impact of these challenges on the burden of disease, however the evidence suggests CALD populations have a higher burden of chronic conditions.15

LGBTQIASB+ community

Members of the LGBTQIASB+ community experience unique health challenges related to their sexual orientation and gender identity.16 Discrimination, stigma, and lack of understanding from healthcare providers can create barriers to accessing adequate healthcare. LGBTQIASB+ individuals have higher rates of mental health issues, substance abuse, and some sexually transmitted infections.17 Additionally, transgender individuals may face challenges accessing gender-affirming healthcare.18

Australians living in rural and remote locations

Australians living in rural and remote areas of Australia face distinct health challenges due to geographical isolation and limited access to healthcare services.19 The scarcity of healthcare facilities and specialists can lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment. Additionally, travelling long distances to receive care can be costly and time-consuming, impacting individuals’ ability to seek timely medical attention.20 Rural populations also have higher rates of injury, suicide, and chronic diseases compared to urban areas.21

Males and females

Gender has a significant impact on health experiences and outcomes. Males generally bear a higher total burden of disease due to premature death, while women face a greater risk of ill health because they tend to survive longer and are more susceptible to chronic health conditions and poor mental health.22 In particular, males experience more than three times the amount of disease burden due to suicide and self-inflicted injuries compared to females. They also experience an increased burden from coronary heart disease and lung cancer, whereas females experience more disease burden from dementia and osteoarthritis.23 Women also have several specific sexual and reproductive health needs that evolve throughout their lives.24 They are also more likely to experience family and intimate partner violence, which directly impacts their health outcomes.25 There is a growing body of evidence indicating systemic issues in healthcare delivery and medical research contribute to poorer health outcomes for women, with disproportionate delays in diagnosis, overprescribing, and inadequate investigation of symptoms.26

Children and young people

Every child in Australia has the right to a healthy start to life, a safe and secure home environment, and equal access to opportunities to help them learn, develop, and thrive. The mental wellbeing of children is imperative to their mental health into adulthood, with children’s mental health currently impacted by a range of social, economic, political, and cultural factors.27 This includes concerns about climate, as children are going to face the full consequences of environmental change, which will have an impact on their health.28 To ensure a safe future and liveable environment for next generations, rapid transformation of energy systems and the economy to reduce the dependence on fossil fuels is needed, with further sustainability in the health system also needing consideration.29 Young people are highly susceptible to the marketing of harmful products, with specific protections needed against the predatory tactics used by the tobacco, gambling, and other harmful product industries.30

Factors contributing to Australia’s high burden of disease

Constrained capacity of Australia’s health system

Australia is facing significant capacity constraints, with major health workforce shortages, increased demand, rising costs of delivering healthcare, and the aftermath of COVID-19, including delayed care and long COVID, and rising costs of providing healthcare. While these capacity constraints have existed for several years, the COVID-19 pandemic shock highlighted these constraints when Australia’s health system was required to respond to a surge in demand. Despite having one of the most well-resourced healthcare systems globally, Australia was not adequately prepared for the scale and complexity of the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, public hospitals were struggling to meet demand before the pandemic largely due to workforce and hospital bed shortages.31 The increased demand created by the COVID-19 pandemic led to delays in elective surgery and outpatient appointments as public hospitals were not equipped with consumables, medical equipment, and appropriate personal protective equipment and protocols, and had limited capacity to scale up and meet increased demand created by the pandemic.

As access to hospitals and other healthcare settings was limited during the pandemic, much of the demand fell onto general practices. General practices had to adapt rapidly to the change in circumstances with many practices transitioning to telehealth appointments, implementing unfamiliar infection control measures, and preparing to deliver thousands of COVID-19 vaccines. Pre-existing shortages of general practitioners meant that general practices faced several challenges meeting the increased demand, with many practices needing to increase their opening hours. Adding more hours per general practitioner, however, was not sustainable, particularly as underinvestment in general practice by successive governments has put a significant strain on practices.

Three years on from the onset of the pandemic, many general practices are struggling to remain viable, the costs of delivering high-quality healthcare are increasing, public hospitals are operating at or over capacity, the nation is facing unprecedented workforce shortages, and there is a major backlog in elective care. The COVID-19 pandemic is still impacting communities, and we are only beginning to understand the implications of long COVID. As much of Australia’s pandemic response relied on the goodwill of healthcare workers ― a group that has gone beyond normal expectations to keep Australia safe ― we are now seeing a surge in healthcare worker burnout. We are also seeing increasing health workforce maldistribution and shortages, with AMA analysis projecting a shortage of 10,600 GP full-time equivalents (FTE) by 2031–32 if strategies are not implemented to attract and retain GPs.32 Additionally, while significant strides were made with respect to telehealth, telemedicine, and virtual care, many of these learnings have not been consolidated for widespread implementation, and many parts of the health system are struggling to become interoperable.

If another pandemic or similar event was to occur in the next few years, Australia would likely be in a worse position than before the COVID-19 pandemic as there is even less capacity in the system now. Despite this risk, Australia is not prioritising investment in expanding capacity to prepare for future events that could increase demand for healthcare services. Additionally, the loss of Health Workforce Australia ― a Commonwealth statutory authority that delivered a national, coordinated approach to health workforce planning and reform ― in 201433 left a significant hole in Australia’s workforce planning capability and has likely contributed to the current workforce shortages and capacity constraints.

Declining access to healthcare

Access to timely and affordable healthcare is fundamental in preventing, treating, and managing health conditions. Access to healthcare services has been an issue in Australia for many years and can be attributed to a complex interplay of geographical, cultural, social, and demand/supply barriers. This issue was only exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with delays in appointments and procedures creating a significant backlog of care.

We are now at a point where more than one in three patients will wait longer than the clinically recommended 30 minutes to receive urgent care in the emergency department.34 One in three patients will also wait longer than the clinically recommended 90 days for Category 2 elective surgery35 ― procedures like heart-valve replacements or coronary artery bypass surgery.36 Waiting times for specialist outpatient appointments are sometimes more than triple the recommended time,37 and it has been reported that wait times for an appointment with a general practitioner have increased over the past few years.38 It has also been reported that patients are waiting longer for essential diagnostic tests, such as medical imaging.39,40,41,42,43,44,45,56

Access to general practice remains a key issue, with shortages of GPs as well as the increasing cost of delivering high-quality care resulting in many general practices struggling to remain viable.47 Additionally, the rising cost of living renders healthcare less affordable for many Australians, and the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) no longer bears any relationship to the actual cost of providing services to patients.48

These access issues create missed opportunities for prevention and early intervention, resulting in patients presenting with more advanced disease and comorbidities that are a direct result of delayed care ― which in some cases requires emergency care ― ultimately making it more challenging and more costly to deliver care.

Complex funding arrangements

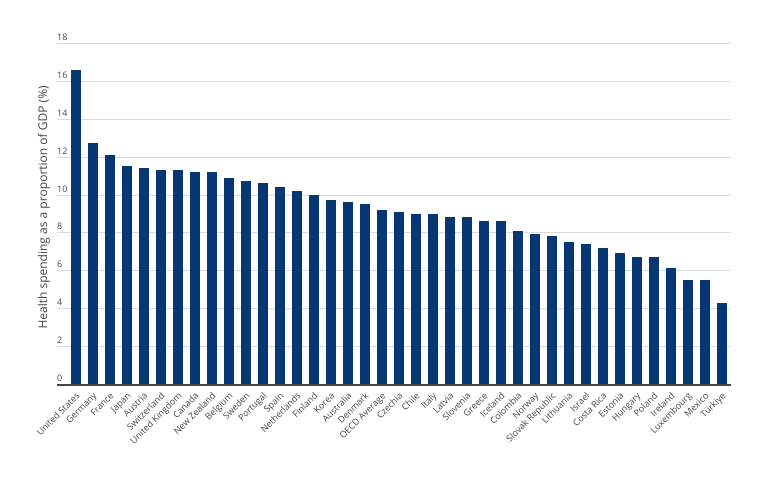

Australia spent $241.3 billion on health in 2021–22, equating to about $9,365 per person and 10.5 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).49 About $176.0 billion of this was directly funded by government, with the remaining $65.3 billion funded by non-government entities, individuals, private health insurers, and injury compensation insurers.50 While annual expenditure on healthcare has been increasing year on year ― largely due to a growing and ageing population that is developing more complex and chronic disease ― healthcare funding as a portion of the federal budget has remained between 15 per cent and 17 per cent for the past 30 years.51,52,53

Compared with other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries,i Australia’s health system appears to be cost effective, with lower healthcare spending compared with many other OECD countries ― including key peer countries Canada, France, and the United Kingdom ― for comparable or better life expectancy (Figure 6).54,55 Australia’s average life expectancy of 83.2 years is the third highest in the OECD,56 with life expectancy at birth in Australia steadily increasing over the past three decades to now be one of the highest in the world.57 This high life expectancy is partially attributable to the high-quality healthcare in Australia, with Australia’s healthcare system ranked third in the Commonwealth Fund’s comparison of 11 high-income country healthcare systems.58

Figure 6: OECD healthcare expenditure as a proportion of GDP, 202259

Average life expectancy is only one measure of health outcomes and is often considered to be a superficial measure as it does not capture factors such as quality of life, disease burden, disability, wellbeing, and health inequalities. While Australia has a high life expectancy, it also has a high number of years spent in ill-health compared to other OECD countries,60 and is lagging compared to other countries when it comes to factors such as prevention of chronic disease and access to care. Additionally, compared with other OECD countries, Australia’s healthcare system is often considered complicated for patients to navigate, which creates barriers to coordinated, high-quality, and efficient healthcare.61

Successive reviews have found that the current governance and funding arrangements tend to be complex, at times inflexible, often fragmented, and typically focused on activity rather than outcomes.62,63,64,65 In particular, the lack of connection between the different levels of government commonly results in duplication of effort and gaps in service delivery and funding, which adds to the complexity of, and inefficiency in, the health system.66,67,68,69 It also results in disagreements and cost-shifting between the different levels of government and the private sector. Previous reviews have recommended refining agencies and their structures to improve transparency and accountability, reduce inefficiencies, improve coordination, and address gaps in service delivery.70

Australia has a “sickcare” health system

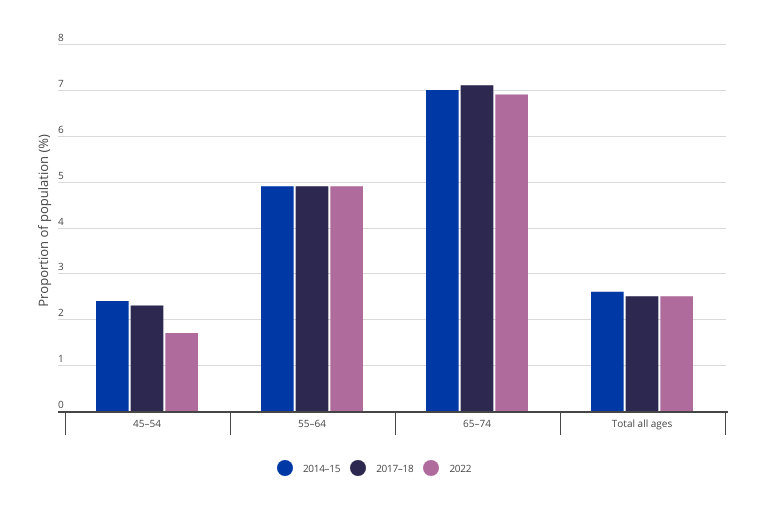

While some chronic diseases are difficult to prevent, such as those with an underlying genetic basis, it is estimated that 38 per cent of disease burden, (49 per cent for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples), could be prevented by reducing modifiable risk factors, such as obesity and being overweight, physical inactivity, poor nutrition, smoking and vaping, and alcohol, tobacco and other drug use.71 Since the Intergenerational Report 2002 — one of the first government reports to examine the whole-of-government fiscal impact of the burden of ageing and disease — there has been an increasing focus on addressing the burden of disease in a few key areas. For example, the burden associated with heart, stroke, and vascular diseases has improved for the 65–74-year-old cohort, and has stabilised for the 55–64-year-old cohort (Figure 7), likely a result of investments in preventive health measures and public awareness campaigns to address obesity and reduce smoking, as well as early intervention for conditions such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol. Similarly, the proportion of the population with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), of which smoking is one of the leading causes, has declined among the 45–54-year-old cohort (Figure 8). This cohort would have been teenagers and young adults when the anti-smoking measures began in Australia, such as the Tobacco Advertising Prohibition Act 1992.

Figure 7: Proportion of the Australian population with heart, stroke, and vascular disease by age group, 2014–15, 2017–18, 202272

Figure 8: Proportion of the Australian population with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by age group, 2014–15, 2017–18, 202273

Despite these improvements, Australia still has the seventh highest prevalence of obesity in the OECD.74 Additionally, rates of smoking and risky alcohol consumption remain high,75 and vaping has more recently emerged as a significant risk factor for chronic disease,76 particularly among younger populations.77,78 Additionally, there are areas that require more attention, particularly mental health. It is clear that while governments recognise the pervasive impact of poor health, healthcare in Australia is still viewed as a cost rather than a strategic investment, which perpetuates a system that predominantly responds to poor health outcomes rather than actively preventing them. This is a significant contributor to Australia’s high burden of disease. This perspective is evident when we examine spending on preventive health, which remains low by OECD standards ― less than two per cent of annual health expenditure in the pre-pandemic years since 2011–12, and about 1.5 per cent in 2018–19 and 2019–20.79,ii There are several interrelated reasons for this lack of investment, including:

- investment in prevention often does not show immediate return

- short-term political cycles incentivise initiatives that will deliver demonstrable short-term rewards, often with a focus on infrastructure, rather than less physical strategies focussed on long-term benefits

- there are challenges in collating the evidence to determine what preventive measures have the greatest efficacy

- there are many sources of funding for preventive health across the various levels of government, reducing the ability to determine the return on investment

- the loss of the Australian National Preventative Health Agency — an independent agency focused on providing evidence-based advice to the federal government and state and territory governments on preventive health and the effectiveness of interventions — in 201480

- healthcare needs and outcomes are not uniform across the Australian population

- preventive health programs often consist of a variety of different initiatives, leading to challenges in identifying those which are most successful, and therefore should be continued and expanded.81

This prevailing paradigm has inadvertently shaped a “sickcare” system rather than a holistic healthcare system that tackles both existing health issues and prioritises prevention. With a population that is growing, ageing, and developing more complex and chronic disease, Australia should be looking at how healthcare expenditure can be maximised to improve health outcomes.

i As a member of the OECD, Australia is assessed against the international standards for healthcare quality and performance and compared against other OECD countries.

ii Spending on preventive health increased in 2020–21 and 2021–22, however this was likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.