AMA History

Since its fractious beginnings as an offshoot of a British parent to a truly Australian member organisation, the AMA has played a crucial role in the development of medicine. Initially established for the sharing of scientific and medical knowledge, the AMA quickly began to involve itself in medical politics – representing the profession’s views on health care and public policy to the governments of the day.

Founding of the AMA

The history of medical organisations in Australia dates back to the early 1800s, when groups of doctors banded together under various names to discuss medical developments and unusual cases. But it was not until 1880 that State branches of the British Medical Association were formally recognised in Australia. The BMA Branches formally merged into the Australian Medical Association in 1962.

Read more about the AMA’s origins in More than just a union: A History of the AMA

AMA crest and logo

Logo

The AMA's logo features a serpent wrapped around a staff - the symbol of Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine. The Ancient Greeks regarded snakes as sacred and used them in healing rituals to honour Asclepius, as snake venom was thought to be remedial and their skin-shedding was viewed as a symbol of rebirth and renewal. It is a traditional symbol of medicine used by many medical organisations around the world.

Crest

The AMA Crest was granted by Kings of Arms (and Supporters by Garter) on 10 June 1963. The serpent and staff also appear on the AMA's coat of arms.

Motto

The AMA's motto – pro genere human concordes – means "united for humanity" or "all as one for mankind".

|

|

Dr Omar Khorshid is an experienced medical leader and orthopaedic surgeon, specialising in arthroscopic and reconstructive surgery of the knee and hip. He was elected President of the Federal AMA on 1 August 2020, and is a past President of AMA WA.

Omar was born in Melbourne and moved to Perth with his family as a child. He completed his medical degree at the University of Western Australia in 1997 and commenced his internship and residency at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in 1998. He completed his Advanced Surgical Training in Orthopaedics and was awarded Fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons in 2007.

After a year as a consultant orthopaedic surgeon at Fremantle and Rockingham Hospitals, Omar spent a year performing Fellowships in Sydney (knee surgery) and Edinburgh (complex joint replacement), before returning to Perth in 2009.

Omar has a longstanding interest in medical education, and was appointed as an Adjunct Clinical Associate Professor at Curtin University’s new medical school in 2016.

While his title is Associate Professor, Omar prefers to be called Dr.

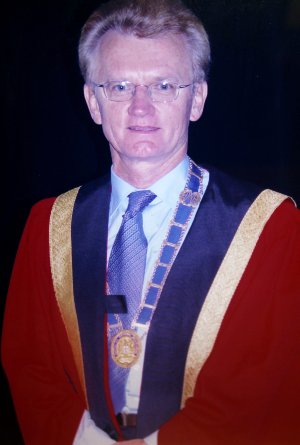

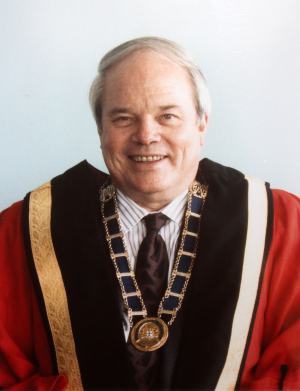

Dr Anthony (Tony) Bartone was elected Federal President of the AMA in May 2018, having served as Vice President since May 2016. He served as President of AMA Victoria (AMA VIC) from 2014 to 2016, and as Vice President of AMA VIC from 2012 to 2014.

Dr Bartone is an experienced General Practitioner and management executive, working in two General Practices in the northern suburbs of Melbourne. His principal specialty interests include men’s Health, mental health counselling, care co-ordination of patients with multiple chronic illnesses, and aged care.

Dr Bartone graduated from Melbourne University in 1984 after completing his residency at St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, and obtained his fellowship with the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners in 1990.

Dr Bartone also completed a Master of Business Administration from the Melbourne Business School in 2004 with First Class Honours average.

Dr Bartone has held many Federal AMA Council and Committee positions since 2008, including serving as a member of the AMA Council of General Practice.

At the 2016 AMA National Conference, Dr Bartone was awarded Fellowship of the Association in recognition of his outstanding services to the AMA and as a mark of the high esteem in which he is held by Fellow members.

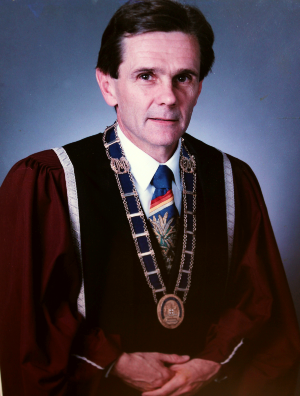

Dr Michael Gannon was elected AMA President in 2016. He was immediate Past President of AMA WA and Head of the Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology at St John of God Subiaco Hospital in Perth.

Dr Gannon is an Obstetrician & Gynaecologist in public and private practice with an interest in medical problems in pregnancy and perinatal loss. He is the Lead Obstetrician in the Perinatal Loss Service at King Edward Memorial Hospital and the RANZCOG nominee to the state Perinatal and Infant Mortality Committee.

He was born at St John of God Subiaco Hospital. He grew up in Perth and was educated at Guildford Grammar School. He lives in Perth with his wife and two children.

Dr Gannon graduated from the University of Western Australia, before training at Royal Perth Hospital, King Edward Memorial Hospital, the Rotunda Hospital in Dublin and St Mary’s Hospital in London.

He is Chairman of the Federal AMA Ethics & Medico-Legal Committee. He has been a member of the AMA’s Public Health Committee and Medical Practice Committee. He is a Member of the Cases Committee of MDA National.

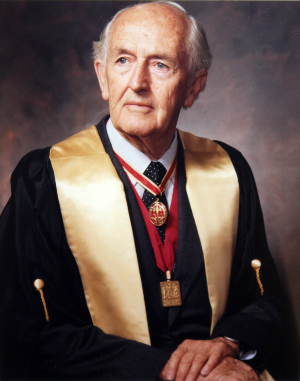

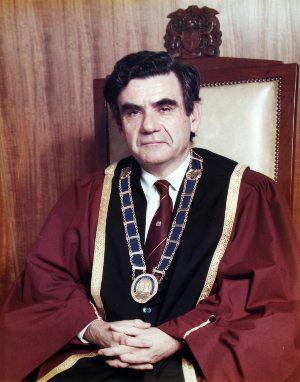

Professor Brian Owler was elected Federal President of the AMA in May 2014.

He is a Consultant Neurosurgeon at the Children's Hospital at Westmead, Westmead Private, Sydney Adventist Hospital at Wahroonga, and Norwest Private Hospital.

Professor Owler has a PhD from the University of Sydney and spent 18 months performing research at the Academic Neurosurgery Unit at the University of Cambridge. He is Associate Professor of Neurosurgery at the University of Sydney.

Professor Owler has a particular interest in public health advocacy. He can be seen on billboards and on television as the face and voice of the “Don’t Rush” advertising campaign targeted at reducing speed-related road accidents in NSW.

Dr Steve Hambleton was elected Federal President of the Australian Medical Association (AMA) in May 2011, after serving a two-year term as Federal Vice President.

Dr Hambleton graduated from the University of Queensland in 1984 and commenced full-time general practice in Queensland in 1987. He has been working at the same general practice at Kedron in Brisbane for 24 years since 1988.

In 1989, Dr Hambleton became one of the principals of Continuous Care Medical Centres, where he developed a strong interest in practice development and teaching medical students and GP registrars. In 2000, he was appointed Medical Director and then State Director of Foundation Healthcare in 2001, which has become one of Australia’s largest GP corporate groups, IPN.

Dr Hambleton is a former member of the Government Red Tape Taskforce and the Practice Incentive Program and Enhanced Primary Care Review Advisory Group. He currently serves on the Practice Incentive Program Advisory Group.

Dr Hambleton was President of AMA Queensland and an AMA Federal Councilor in 2005/2006 and for a short period was Acting CEO of AMA Queensland. He has served on the AMA Council of General Practice at a State and Federal level for more than a decade. Dr Hambleton was the AMA representative on the National Immunisation Committee from 2006-2010, and was a member of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee for two years until 2009. He has been a member of the AMA Taskforce on Indigenous Health since 2006 and is currently the Chair of the Taskforce.

Dr Hambleton was admitted as a Fellow of the AMA in 2007.

He is married with four children.

AMA President Breakouts: Reforming Health Care

It is indeed a great honour for all AMA presidents to represent our profession and, in a sense, be seen as the public face of the medical profession.

Without doubt, the defining issue for the AMA and my Presidency was the health reform agenda of the Rudd Labor government. Rudd had correctly identified the widespread dissatisfaction from patients and health professionals with the increasing failure of the health system to cope with the community’s healthcare needs.

Identifying that a problem exists is one thing, fixing it is another.

The AMA did its best to help steer the reform process in a direction that would allow doctors to deliver the best care that they could for their patients, while not themselves having to pay the price of health reform. It was important that the AMA was seen to be part of health reform, rather than an obstacle to it.

History will judge the success or failure of the health reform initiatives. At present, it appears that the only significant outcomes of the process were to introduce activity-based funding in those states where it had not previously been used, and the move to increase local decision-making via the appointment of local governing councils to oversee local management of health district hospitals. Medicare Locals provide an opportunity for sensible structured assistance to our long-suffering general practitioners, but also for difficulties if they are not properly run.

It was inspiring to me to see the passion and dedication of doctors at all levels and our AMA secretariat work to improve the health system.

I was proud of how they rose to the challenge of working with sometimes unsympathetic political and bureaucratic systems to provide constructive solutions to problems not of their own making. For example, the AMA’s consensus document on training of the future medical workforce remains the single concise template for an effective training system from medical school intake to vocational specialist training, which will provide the doctors that our communities need.

The opportunity to promote and advance the cause of a National Disability Insurance Scheme was a personal highlight. A journey that for me had begun a decade earlier as a struggle to address the unaffordability of the medical indemnity insurance system now took on more widespread significance as the AMA championed support for disability based on need rather than blame.

The Productivity Commission delivered visionary and aspirational recommendations recognising that the political realities of a federated system should not forever condemn Australians with disabilities to fragmented and inadequate support. An opening now exists for a once-in-a-generation opportunity to progress a problem that has remained in the too-hard basket for too long.

Should a National Disability Insurance Scheme proceed, I believe all AMA members can be proud that the AMA played its part in assisting our most vulnerable patients.

Dr Andrew Pesce: AMA President 2009-11

AMA President Breakouts: Standing Up for the Profession

Becoming Federal President of the AMA was never a specific goal in my life, but rather an evolution of passion and commitment.

As leader of the AMA, you are able to serve your profession and patients across the spectrum. As President, you are the servant and your master is high quality, equitable, clinical care for Australians, ensuring that the medical profession can practice its craft with responsibility and clinical independence.

It is a role that should always be observed with humility.

It is a role that represents the entire profession and must not be affected by vested interests. It is a role that should be underpinned by patient care as a priority, utilising tax dollars efficiently and effectively for healthcare delivery.

My Presidency commenced in 2007 with the secretary general’s position vacant and a federal election five months away. It was like being chair of the board of a major company facing a critical time in business, with no chief executive officer. The AMA relies on the intellect, ability and hard work of good staff, and the overwhelming voluntary contribution of colleagues. On these shoulders we were able to continue to do business, but it was an additional challenge.

During the election lead up, the AMA made health a pivotal issue and it was a hot contest between a government facing loss and an opposition striving for power. That election and the change of government was an exciting time to be a federal president. Many current issues are a legacy of policy proposals debated then, and the AMA’s ability to influence is essential for better outcomes.

A good example is a headline story in The Australian on 5 March 2012 when the new health minister allowed up to 10 ‘health professionals’ prescribing rights under the Australian Health Practitioners Regulation Agency (AHPRA) workforce improvements. This ongoing ‘deregulation’ of quality healthcare for Australians was borne out of the concept of national registration.

Initiated by the Howard government, this legacy is based on lowest common denominator ideologies rather than recognition of the requirement for training, standards, and complexity of skills to deliver optimal care based on expertise. We continue to suffer the afflictions of AHPRA on medical practice and care.

During my term as President, we finally enlightened then health minister, Tony Abbott, and subsequently the prime minister, that this national registration model was convoluted, bureaucratic and expensive. The AMA was instrumental in stopping John Howard from signing the intergovernmental agreement.

There was an interval pause for some sense to be applied but, with a change in government, Kevin Rudd hurriedly went ahead. Many have experienced the inefficiencies and costs of this system of registration, and the ongoing repercussions to the medical profession. More importantly, our patients are being shortchanged with attempts to con them into accepting that ‘medicine’, while ‘diagnosis’, ‘prescribing’, ‘clinical management’ and ‘investigation’ can be delivered by a range of health professionals to the same intellectual ability and safety as a doctor.

At election time, the AMA had to hold the parties accountable with regards to bed shortages, emergency department overload, hospital occupancy, cost shifting, health funding, general practice infrastructure, rural health services, Medicare, training, public–private split and, of course, party ideology.

Misdirected drivers to pork barrel electorates with Super Clinics; babies put at risk with a push for home births that made mothers feel inadequate if they chose a hospital; the ‘buck stops with me’ and Nicola Roxon’s 2008 Ben Chifley Memorial Light on the Hill speech, as health minister – these were all at play during my 2007–09 Presidency.

In the 2012 Labor leadership battle, Roxon’s references to Kevin Rudd, which – according to The Australian – “revealed the depth of this shambolic policy-making” in health, were an insight into those times.

We have an AMA for a reason. We must never assume that government policy should not be questioned, challenged and informed by service providers at the coalface who understand what is needed and what can be responsibly and sensibly provided.

So, in my Presidency, to be constantly analysing and questioning, to be putting forward alternative, more effective and efficient solutions, and to be pushing hard against the juggernaut of a confident new government bureaucracy, was energising. Bringing together our colleagues across colleges and craft groups was important. We achieved this across the medical profession, and even across the allied health providers on the issue of the AHPRA model.

Federal Presidency is a learning curve across all issues. The big picture is as important as attention to detail. You need to be able to stand in the face of attack, and stand on principle for the profession, not for yourself. The reward is the experience and the privilege.

Dr Rosanna Capolingua: AMA President 2007-09

AMA President Breakouts: A Long Illustrious Line

It is with great pleasure as the 19th President of the Federal AMA that I write to contribute to the celebration of the 50th anniversary of our great Association.

My thoughts are about the giants on whose shoulders I have stood.

The spectacular changes in health, healthcare, health delivery, safety and quality, and public health that the AMA has brought in its time have been a collective effort over many years with many significant contributions. It is the work of the many that brings the accomplishments of the AMA and its presidents into the light.

In my case, the line of presidents I was guided and influenced by is long and distinguished. Each brought their own style and made their own marks on the medico-political landscape.

I worked tirelessly to build on the work and the contributions and the changes and improvements of my predecessors, adapted and applied them in the contemporary environment of my Presidency, and shaped a new AMA manifesto to pass on to the formidable presidents to follow me.

I was a voice for grassroots members and was always available to them, the Association, and the profession to be a strong advocate to the government. I learnt a lot.

My passions in office were to meet the people in each part of our great land. Our very talented members – my colleagues. They are all fierce defenders of their patients and masters of their own destinies, staunch advocates for health and their part in it. Fearless but fair proponents for a better deal for justice in health for all, they were always fun to be with.

There were big issues to deal with. I played a part in consolidating the benefits to doctors, patients and communities from taming the ‘mammoth’ of the medical indemnity crisis, which spanned many years. I championed public health through promoting awareness of issues such as pandemic influenza (bird flu in my day), childhood obesity, immunisation (including HPV), the great increase in anaphylaxis and improving the safety of those with it.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health was a special interest of mine. The AMA expressed strong public concern about the ability of the Northern Territory Government to look after the health of its people. This led to urgent meetings with the NT government, including with the Chief Minister.

It was soon after this that the Federal Government’s Intervention rolled into the territory, vindicating AMA concerns.

The merits or otherwise of the Intervention are still being debated.

We also questioned the Work Choices legislation and the veracity of the heart tick, when a high calorie food manufacturer was granted a tick to a few products leading to a halo effect on its other products.

Politically, supporting the private health sector and promoting informed financial consent successfully kept new legislation at bay. The Medicare system’s many changes – including changes to care planning and nurse rebates – and the addressing of the burgeoning medical school training posts and the surge in unfunded bonded medical student places were tackled. So too was the poor access to medical services in rural, regional and remote Australia. The AMA also confronted the dastardly spectre of medical racism, which involved taunting of international medical graduates after well-publicised cases of poor medical practice around the country.

The AMA’s serious incursion into e-Health began with its National e-Health Conference in Old Parliament House, progressing e-Health in general practice with the Practice Incentives Program incentives (among other enhancements), and an analysis of the readiness of specialists for e-Health. The use of new technology for using the services of Medicare was progressed, but the ill-fated Access Card was laid to rest as the parameters around it became unacceptable.

My trajectory since the Presidency has been, in my opinion, directly due to my roles with the AMA at state and federal levels. The prestige and high regard given to the AMA as the peak membership driven organisation representing the breadth of the medical profession – albeit sometimes begrudging and fearful – was absolutely instrumental in my various appointments post-Presidency.

The accompanying kinship, friendship, support and respect afforded me is not something I would ever take lightly. I feel I have been very fortunate to have the opportunity and the confidence of my peers to represent them and to promote their agendas and the best interests of the profession and the Australian people.

It was an honour to lead the AMA.

Dr Mukesh Haikerwal: AMA President 2005-07

AMA President Breakouts: Getting the Message Across

Can you imagine a time when up to 20 per cent of the medical profession was being sued, most of whom had never been sued before, and most of whom were not guilty of medical neglect?

Can you imagine a time when nearly every obstetrician, gynaecologist, and neurosurgeon was considering leaving their profession because of either the fear of being sued or actually being sued?

Can you imagine a time when irresponsible plaintiff lawyers were running amok across the health system sucking the goodness out of the hearts and souls of the medical profession?

Can you imagine a time when the medical indemnity industry was brought to its financial knees and put into voluntary liquidation?

Can you imagine a time when more than 5000 doctors would turn up to the Randwick Racecourse in Sydney saying “enough is enough”?

That time was my Presidency of the Federal AMA from 2003 to 2005.

Never before was the profession so united behind one single cause. The state AMAs, the craft groups, the colleges, the societies and, more importantly, the public in general stood firm to make the government realise that circumstances had woken the sleeping giant – the medical profession.

The medical profession often reminds me of a big brown bear hibernating – it takes a lot to wake it up, but if you prod it, poke it, and pull its hair, it will eventually stand up and take out those who stand in its way.

Although the medical indemnity crisis represented dark days for the profession and for our patients, it united us in a way that we probably have never seen before and may never see again.

The outcome of the rally and mass meeting at Randwick Racecourse, where the AMA NSW chief executive officer, Laurie Pincott, was a driving force, was the replacement of health minister, Kay Patterson, with Tony Abbott.

Over the subsequent days and weeks, the AMA and the profession worked very closely with the Howard Government to find a solution to this crisis. I have to acknowledge a number of people, both within the AMA and within government, who delivered what I believe was, and is, a sustainable but fair outcome for both patients and the profession.

The new health minister, Tony Abbott, drove the medical indemnity solution from the top. He worked personally, first hand, to solve the crisis.

The Minister was ably supported by his chief of staff, Maxine Sells, and other key players. I would like to particularly acknowledge John Perrin (now deceased) from the Prime Minister’s Office and Health Department Secretary Jane Halton, who was backed up by David Kalish, Louise Morauta and Rosemary Huxtable, who all worked with the Minister’s office in designing a way forward.

Our AMA team, led by Dr Andrew Pesce, worked tirelessly with all parties concerned to deliver the ultimate outcome.

The shadow health minister at the time was Julia Gillard, and she remained supportive through the whole process.

I would also like to acknowledge the state presidents, the CEOs and Dr David Molloy from Queensland, who led the tort law reform agenda at the state level. AMA Queensland CEO, Kerry Gallagher, AMA Western Australia CEO, Paul Boyatzis and AMA Victoria CEO, Dr Robyn Mason need to be singled out for the outstanding roles they played in both the federal and state reform agendas.

My Executive – vice president Dr Mukesh Haikerwal, Dr Dana Wainwright, Dr Rosanna Capolingua, Dr Andrew Pesce and Dr Choong-Siew Young – helped manage and carry the medical indemnity and other issues across the country.

Dr Mukesh Haikerwal was my right-hand man and handled all issues relating to primary care. He was and continues to be a wonderful friend and supporter of the profession of medicine. Pam Burton, Roger Kilham and John O’Dea at the AMA Secretariat provided the legal, economic and policy backbone for our Executive and Council to be fully briefed across all issues of interest.

At the same time, many of this same group worked with me and the AMA to deliver the Safety Net which, despite some more recent watering down, still continues to provide great support to a significant number of patients and makes the Medicare system more like the system that was originally intended.

One of my major highlights during my term as the AMA President was to meet and work with John Flannery, the head of the Federal AMA’s Media and Public Affairs Department. He taught me so much about how to get a message across to politicians, the media and the public.

His message was always simple, clear, and always picked up by the press gallery, the national media, and the medical press. I am indebted to him for his support during my term.

Dr Bill Glasson: AMA President 2003-05

AMA President Breakouts: Informing the Public

I became AMA President at the turn of the century – 2000 was a fortuitous time in Australian medical politics. The medico-political landscape was tough, divided, and complex.

The big issue was the medical indemnity crisis. We were at risk of losing entire specialties like obstetrics and neurosurgery. Procedural specialties would have become uninsurable and unaffordable. Major indemnity providers were at risk of imminent bankruptcy.

Yet we were faced with a health minister who did not want to know about it. Blocked by the minister, Michael Wooldridge, we had to find a way to get the Government’s attention. The public picture was one of a bitter feud, but I just needed to focus the government on this issue.

We engaged every member of both Houses of Parliament until then prime minister, John Howard, eventually became convinced that this was an issue of national importance.

Working directly with his office, and through a taskforce involving every state and territory government, we forged a long-term solution through scaffolding of the existing system and tort law reform to reduce the level of litigation that was plaguing the effective delivery of medical services.

One of the things I sought to do as AMA President was to inform the Australian people about their health system – how it worked, where it was successful, and where it fell short of reasonable expectations.

The Australian public became, through the media and directly through their doctors, a far more informed participant in the Medicare debate than they had ever been.

What resulted was a more sophisticated understanding of how health funding and bulk billing work, who ultimately pays, and why doctors were so concerned about the level of funding failing to keep up with a growing and ageing population. No longer could governments of any persuasion get away with the old ‘greedy doctor’ argument.

When I became AMA President, we were being told there was an oversupply of doctors, yet this was at odds with information from our members and from the public. We commissioned our own modelling and were able to demonstrate that the workforce figures were wrong. In fact, there was an undersupply in critical specialties like general practice. We were able to convince the Government to change the way they assessed the medical workforce to plan more appropriately for future needs.

The Government could no longer use a mythical oversupply as an excuse for draconian or inappropriate workforce policies.

We took the message beyond the major centres to rural and remote parts of Australia.

We were also perennially frustrated with the costshifting games being played by successive state and federal governments, so I coined the term “blame-shifting” to focus attention on the way that different levels of government attempted to foist responsibility for health funding shortfalls onto the other levels. That is still unresolved.

Along with the battles about health funding, workforce supply and tort law reform, I was determined to pursue a parallel public health agenda.

The Australian medical profession has a long and proud history of advocacy for public health, and the AMA was ideally positioned to contribute. During my Presidency, the AMA team:

- developed a Position Statement on Climate Change and Human Health;

- developed a Position Statement on Complementary Medicine;

- addressed the issue of preparedness for bioterrorism;

- created the AMA Indigenous Health Report Card;

- developed a Position Statement on Sexual Diversity and Gender Identity; and

- worked to improve the occupational health and safety of young doctors with the Safe Hours Project.

While we worked closely with the Government on a raft of major issues, we also kept up the pressure with a unified message and a sophisticated media campaign of constructive commentary, positioning the AMA as the powerful independent voice of the medical profession that it always must be.

Professor Kerryn Phelps: AMA President 2000-03

AMA President Breakouts: Engaging with Government

While my Presidency lasted from 1998-2000, my active involvement with the AMA began in 1990. It was 10 turbulent years.

For general practice, it saw the introduction of the Vocational Registrar (an important step in the formal recognition of general practice as a specialty), the Practice Incentive Program (the first non-fee-for-service government remuneration for general practices), financial incentives for performing and recording vaccinations (a highly successful public health program) and the formation of divisions of general practice (later GP Networks and now Medicare Locals).

There were incentives to try and improve the rural GP workforce, GP-based research, and ongoing debates about just how many GPs we needed in Australia.

Many of these changes started with the General Practice Reform Strategy in 1992 and were revised in detail with the involvement of the AMA and other GP groups in the General Practice Strategy Review launched by the then health minister, Dr Michael Wooldridge, in 1998.

Private health insurance and concerns about US-style managed care were major issues for privately practising specialists. The Private Health Insurance Rebate was introduced during the term of my Presidency. The rebate was hard fought for, and with no certainty to succeed in a Senate where the Liberal Government did not have the balance of power. Nogap private health insurance products were also introduced under which the majority of private hospital services are now provided.

And ticking away in the background was the Relative Value Study, a probably always ill-fated process that involved countless hours from doctors and consultants, the political management of which was like trying to keep chunks of fissile material apart before they came together in a supercritical mass to blow the profession apart.

These were interesting times indeed.

The AMA supported many – but not all – of these changes. Some of the ones we opposed were introduced anyway with the support of other medical groups.

As the government moved ahead, I believed the AMA was faced with a clear choice. Either get on the playing field and engage the government and try to slow or redirect some of these changes, or remain a noisy spectator shouting insults at the referee but not changing the course of the game.

Not all AMA members agreed with that course of action.

Despite widespread consultations, sections of the profession continued to oppose engagement and change.

In addressing that discontent, it is important to understand there was a clear mandate.

I did not become President by accident or subterfuge. My view on how we should proceed was put forward at Federal Councils and National Conferences and was my consistent platform. Every time I stood for an elected position in the AMA it was contested, giving those who voted a clear choice between my approach and that of the opposition. That culminated in 1998 when I became Federal President, defeating the incumbent president. That win stemmed at least in part from a desire by National Conference to engage the government.

That engagement was always underpinned by the AMA’s basic principles – the professional freedom to always provide care in the best interests of our patients, and the right to charge a fair and reasonable fee independent of any government or private health insurer’s interference.

Despite the consultation and re-election of the Executive at National Conference, the opposition continued. After being challenged to put up or shut up, those opposed to our approach sought to remove the entire executive at an Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) of AMA members. Two EGMs later, the Executive, already elected by National Conference, was endorsed by the full membership.

These were turbulent times and I could not have survived without the support of my Executive, Federal Council and, perhaps importantly for my sanity, the unwavering support of my family.

Perhaps time has dulled my memory but, despite the upheavals and the near total destruction of my solo general practice caused by constant absences, it was a great time to lead a great organisation.

In 1993, the then prime minister, Paul Keating, described the AMA as, “The greedy doctors who are represented by the most rapacious union boss in the country”. In 2006, in the last survey of federal politicians’ lobbying preferences, the politicians voted the AMA the top Canberra based lobby group.

If I were part of leading the AMA from where it was in 1993 to the respect it enjoyed in 2006, and I believe it enjoys still, then all the elections and all the EGMs were worth it

Dr David Brand: AMA President 1998-2000

AMA President Breakouts: Medical Politics

My pathway to the Presidency commenced on a fateful Thursday evening when I went home to have dinner with my family rather than attend a clinical staff meeting at Fremantle Hospital. In my absence, I was appointed the AMA hospital representative.

My eyes were opened to the world of medical politics. I found it useful and productive to work with like-minded doctors to contribute to the broad area of medical practice. It quickly became clear that the Government was not our friend but a serious competitor in directing the future of medicine.

The requisite training program to deal with awesome structures of government included a long period of training by Peter Jennings, a remarkable state AMA employee who spent his professional career representing our interests to government and other bodies.

The move into the Federal AMA was not straightforward given the lack of any direct flights between Perth and Canberra. I settled into a regular pattern of catching the midnight horror to Melbourne with the aid of Temazepam, one hour in the lounge to breakfast and shower, then a short hop to Canberra where I would usually be the first person to turn up for the morning meeting!

There was only one serious hiccup when I called the renowned Rohan Greenland to ask why he was not there to pick me up at the Canberra airport, only to be told that the meeting was at Sydney airport. Fortunately, the shuttle got me to that meeting on time as well.

I remember my sense of surprise when Brendan Nelson, our best known president, approached me at a social function and encouraged me to look towards a position as federal president. With his sudden elevation to serious political life, I was then elected to follow David Weedon and his environmentally focused term.

Not unexpectedly, the main issues during my terms involved conflict with government to the extent that the then health minister, Michael Wooldridge, eventually closed down communications.

The junior doctors had to deal with the provider number issue. They rightly perceived this as a setback for their career prospects and there was a broader concern within the profession that the restrictions on medical practice held by government would be used to conscript doctors to unattractive positions. Junior doctors were magnificent in responding to calls for industrial action and came close to defeating the legislation but were undermined at the last minute by the Australian Democrats. However, as a result of the strength of their protests, a series of governments since has trod warily in attempting to coerce Australian graduates. The Australian Democrats disappeared subsequent to that betrayal.

To my surprise, the other great issue that arose was the attempt by the health funds to introduce US-style managed care into the private hospital system. Fortunately, the surgeons had been well trained by Bruce Shepherd to protect their interests (and those of their patients). What started off as an offer of substantially higher payments in return for a degree of control over surgical practice by the health funds ended up being no more than higher payments from the health funds – not a bad outcome for the medical profession.

But my best moment came at a dinner with Michael Wooldridge and representatives of the private hospital industry. We took to him the concept of lifetime health cover whereby health insurance premiums would be steadily increased for late entrants to the system. To his credit, Michael introduced the proposal (despite advice that focus groups hated it). That single component of the changes to health insurance produced a 50 per cent increase in membership in private health funds and helped underwrite the future of our private hospitals and private surgical colleagues.

My period as president ended when I was defeated by my vice president, a general practitioner. To his credit, he organised a very successful campaign to recruit the eastern states’ members of our electoral college. My disappointment at missing out on another year of travelling to Canberra once or twice a week was modest. I remain a proud supporter of the AMA and am especially pleased that we have had such a magnificent variety of federal presidents to add flavour and diversity to the organisation.

Dr Keith Woollard: AMA President 1996-98

AMA President Breakouts: Reluctant Conductor

In the latter years of my term as Honorary Secretary of the Queensland branch, and as its President (1983-84), I had the opportunity to attend the Federal Assembly of the Australian Medical Association. The highlights of the meetings (for a newcomer) were the enforcement of strict rules of debate and the humour associated with the daily motion to “suspend so much of the standing orders that would allow smoking to occur” for the remainder of the afternoon.

In my early years as a delegate, I was surprised that this motion passed, let alone that it was even being considered. The ventilation in the venue, the Senate Room of the University of Sydney, was suboptimal, and as the meeting progressed the atmosphere became putrid. Eventually, after several years on Federal Assembly, I was pleased to be present when the motion was lost and smoking was outlawed by the Assembly.

After an absence of about 12 months from the federal scene, I was surprised to receive a call in 1988 from Dr Bruce Shepherd, who urged me to nominate for a position on the Federal Council as the pathology representative. I accepted, probably because of my susceptibility to flattery, rather than based on any real desire to start a ‘career’ in the federal arena. Such was not to be. A few years later, I joined the Federal Executive. As Vice President from 1993-95, I watched in awe as Brendan Nelson as Vice President, and then President, captivated his audiences on numerous occasions, even cynical members of the medical profession. His handling of the press was truly amazing and I marvelled at his ability to think on his feet, and control all situations. This job was not for me, I remember thinking frequently.

All was to change. Brendan decided to throw his hat into the political ring by nominating as a candidate for the Liberal Party for the federal seat of Bradfield in 1995.Nominations for the presidency of the AMA closed on the Friday, a day before the selection of the candidate in Bradfield. I agreed to nominate, along with Brendan, for the position of President of the AMA. If Brendan was unsuccessful the following day (for which I prayed), I would withdraw my nomination and he would continue on as a very effective AMA President. I thought I was reasonably safe, particularly when some sections of the media turned on the prospective Liberal Party candidate, for reasons that are probably best not canvassed here.

To my surprise and horror, I received a call from Bruce Shepherd at noon on the Saturday. He said he had “good news”: Brendan had won preselection and I would be AMA President. The reluctant President was soon filling very big shoes. I hated every second of the ensuing year, but tried not to show it.

Only two incidents of that ‘hell year’ remain in my mind:

- a visit to Kirribilli House to meet the Prime Minister of the time, Paul Keating. He was so different to his public image. I will always remember his informal manner, his politeness to a potential thorn in his side, and his frank assessment of all health ministers that he had encountered; and

- becoming lost in Parliament House and the then health minister, Dr Carmen Lawrence, asking me if she could “show me the door” (in good humour).

I have a personal rule that I try to keep. Never return to an organisation that one has previously served. Accordingly, I will not be at the launch of this book, for which I apologise in advance. I broke that rule once in the AMA, and regret very much my brief return to chair an extraordinary meeting of the AMA. Each ‘side’, including me as chair, had legal advisers in attendance and the meeting achieved little, and soon was adjourned.

Hopefully, after serving for 23 years in AMA politics, I have learnt one thing – how to chair a meeting. It is like conducting an orchestra – if the wind instruments are too loud, it is essential to silence them; if the violins are too soft one needs to bring them in (to the discussion). There is no place for the beating of drums in an orchestra or meeting. My baton has now been laid to rest.

Dr David Weedon: AMA President 1995-96

AMA President Breakouts: Setting the Agenda

Four months after Bruce Shepherd placed the chains of office on my shoulders at the 1993 AMA National Conference, I gave my first address as president to the National Press Club in Canberra. I had thought long and hard about what to say, the direction in which the Association needed to go, and my own beliefs about what had to be done. And so I laid out the agenda – the critical importance of an independent medical profession, the consequences to health care and its financing of universal bulk billing, and the crucial role played by private healthcare and insurance to an effectively functioning hospital sector.

But in addition to these core issues, I laid out an AMA agenda in Aboriginal health, environmental health, the human and health effects of unemployment, discrimination against women in the profession, illicit drug use, immunisation, youth suicide, euthanasia and gay law reform, among others. The AMA would be a voice for those with neither power nor influence, reflecting in what it said and did the profession’s commitment to an ethic of service to others. In leading the Association, I would not be ‘safe’.

That day I also held to the cameras a packet of Winfield cigarettes in one hand and Ratsak in the other. I asked why the warning on one killer of Australians was a barely legible note about its impact on fitness, while the other, in ‘black on gold’, told its consumers exactly what it did – “kills rats and mice”. Hours later, then health minister Graham Richardson rang to concede that the Commonwealth would finally move on explicit health warnings on tobacco products. There were hundreds of calls to the Canberra office that day of support and of membership enquiries. Bruce Shepherd rang and simply said, “great job mate, I’m proud of you”. This was a period of immense change and transformation for the Association.

Among the many changes were the AMA-led development of the Professional Services Review, bedding down the nascent Divisions of General Practice, establishing the AMA Council of General Practice, the move to commence the Relative Value Study, and agreement on the concept of ‘informed financial consent’ prior to surgery.We also convinced the new Health Minister, Graham Richardson, of the need for government to encourage private health insurance. Richardson famously called on then Prime Minister, Paul Keating, to take out private health insurance.

The AMA employed its first Indigenous health adviser, successfully campaigned for responsibility for Aboriginal health to be removed from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission and placed into the Health Department, seeded establishment of the Indigenous Doctors’ Association, facilitated changes to medical education to increase and support increased numbers of Indigenous students, campaigned for increased resourcing of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations, and encouraged support for specialist services in Indigenous Australia. The first Indigenous artwork for the AMA was commissioned but, most importantly, Aboriginal health was made a mainstream health issue by the AMA. I made numerous trips to remote areas of the nation with colleagues and politicians to show middle Australia the existential despair, disease and premature death occuring in much of Indigenous Australia. It would not be until 2007 that a government would declare the national state of emergency that the AMA had called for in 1994.

A great deal of effort was invested in tobacco control. In addition to explicit health warnings on cigarette packets, the prohibition of tobacco sponsorship of sport and early bans on smoking in public places, in 1994 we did something that has literally changed the world. In 1994, I successfully moved on behalf of the AMA that the World Conference on Tobacco and Health in Paris adopt a resolution calling for a United Nations strategy on tobacco control. This was subsequently embraced by the UN as the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the global template for action on tobacco control.

My young family sacrificed much to allow me to serve the AMA. We lived in Hobart and I literally spent half the year on the mainland. I juggled GP locums and many nights doing house calls in the satellite suburbs of the city with the leadership of the AMA, on many occasions having little or no sleep. I did not appreciate just how hard – or rewarding – those two years were, until it all finished in May 1995.

To Bruce Shepherd, David Weedon, Priscilla Kincaid- Smith, Ross Glasson and many others, I owe a debt that can never be repaid. But the great sense of privilege and pride I felt in leading and representing the medical profession will never leave me.

The only medical organisation in Canberra that counts – really counts – is the AMA. Its influence and respect relies entirely on the strength of membership, quality of leadership and, above all, a commitment to the nation’s best interests and health transcending all else.

Dr Brendan Nelson: AMA President 1993-95

AMA President Breakouts: Let the Battle Commence

These were tough years to be AMA President. The previous decade had seen the Labor governments in New South Wales and Canberra aggressively pursue, with intent to destroy, the independence of the medical profession. Then-premier, Neville Wran, had told me at our first meeting, “Doctor Shepherd, you represent the last independent group in society. As such I will move to control you.”

In a pincer movement, Neil Blewett was in Canberra using federal legislation to restrict our right to treat private patients in public hospitals as he simultaneously sought to bring general practice to its knees with bulk billing. Governments started funding rampant medical consumerism. This emergent group of predators considered patients as ‘clients’ and professional standards as the domain of their relentless activism. Our profession had given our nation the highest standard of care in the world, yet we were besieged as the enemy in some kind of class war.

The Australian Doctors Fund, established in 1988, was an essential complement to the AMA, focusing as it did on issues as diverse as the decriminalisation of healthcare, the looming crisis of medical immigration, AIDS and road trauma. It would later support the courage of plastic surgeon, Cholm Williams, in his legal battle to have patient records remain the property of the doctor.

My critics forget that we were dealing with a government that had withdrawn all support for private health care, telling Australians that Medicare was all they needed. Senior members of the same government readily used the private hospitals I had worked so hard to defend and for which access to the poor was diminishing thanks to government policy. Then-health minister, Brian Howe, finally offered a Medicare co-payment in 1991. At first we thought we had finally broken through. With Bob Hawke’s support, Howe announced there would be a patient co-payment. However, on closer examination, he was actually planning to cut the Medicare benefit for patients who paid their fees and shift half a billion dollars a year out of health to play with cities. We said no. Paul Keating used it to knock off Bob Hawke. Sir William Keyes was the Keating government’s head of the Office of Overseas Skills Recognition. He told the AMA National Conference in 1992 that any overseas doctor should be allowed into Australia. When challenged if that might, for example, extend to a Pakistan-trained neurosurgeon, he replied “yes, the market should be allowed to sort it out”.

In October 1992, Brian Howe had told us not to bother telling him what the government should do. He said that if we wanted to change what the government was doing, we would have to change the government. Although I was not often inclined to take Howe’s advice, I did on this occasion. We worked tirelessly in support of John Hewson’s Fightback! His health policy restricted bulk billing to pensioners and the unemployed while allowing private health insurance for outpatient services up to 85 per cent of the AMA fee. Families would get means-tested assistance to buy private health insurance. I took the view that if you were not prepared to fight for that then the AMA should pack up its tent and go home.

I battled corporatisation of health care and the profit motive of those who wanted to bring our younger colleagues to servitude in medical emporia. Rural doctors were a major focus, until then receiving scant regard from Canberra politicians and bureaucrats who considered them their masters. Amid all of this, we fought tobacco companies to get them out of sport and off television. Although Jeff Fenech was a mate and patient, we argued the case to better regulate boxing. Fred Hollows was another mate who put his heart and soul into Aboriginal blindness. Inspired by this and the neglect of the Government, I asked Gordon Briscoe to address the Federal Council in 1992. That started us on the journey of Aboriginal health.

I felt that by the time my three years ended in 1993 that I had played a role in building the AMA into a modern effective organisation. It would –and should – be one to be feared and respected.

Dr Bruce D Shepherd: AMA President 1990-93

AMA President Breakouts: Search for Unity

Presidency of the AMA led me to valued friendships and down paths that proved challenging.

The major challenge was to review the Articles of Association of the AMA (adopted in 1962) and render them relevant to the changing needs of the profession and the community. My Presidency began in the wake of the New South Wales hospitals’ dispute and the disunity within the profession that followed.

The Hawke Labor Government introduced Medicare in February 1984 with the inherent threat of nationalisation of medicine included in the legislation that granted the Minister unfettered power over doctors’ fees in hospitals. The dispute was eventually resolved to the AMA’s satisfaction in early 1985 but it clearly demonstrated the increasing importance of the rapidly expanding specialty groups and the need for them to have a voice in decision-making at a political level.

This had to be acknowledged within the AMA structure. Although deficiencies in its constitution had been recognised for some years, the branches remained implacably resistant to any dilution of their powers. The state branches then exerted almost total control over the Federal AMA where there was no craft group representation. My three-year term was largely consumed by a search for unity within the profession, a search that led eventually to a successful major review of its outdated constitution. Sir Robert Cotton, a distinguished businessman, politician and diplomat, agreed to undertake a review and present a report on the structure, function and constitution of the AMA. The 200-page Cotton Report was delivered in March 1987. Recommendation 2 was critical. It stated “that the AMA becomes a national organisation and the autonomy of the Branches be removed”.

An intensive, exhaustive exercise followed to explain and discuss the report’s recommendations to all members of the profession. This process strongly reinforced the need for closer involvement of the expanding specialist groups, especially the Royal Clinical Colleges, which proved vital in the subsequent successful creation of a far-reaching blueprint for the future. Regrettably, but understandably, it was not achieved without bitterness, anger and frustration within some sections of the profession. Bulk billing and its inherent temptations, fraudulent billing and alleged overservicing of patients appeared with the introduction of Medicare. The setting up of fair monitoring systems and the collection of meaningful data remains a problem for the Association 25 years later.

From the outset, the AMA has advocated early professional involvement in the review process. Public challenges by government over alleged excessive medical fees and incomes occurred on a regular basis. It was the time of ‘national wage restraint’. Although the attacks were largely based on the misuse and distortion of data, responding to them required a lot of attention. It was a volatile time. Confrontation with government over fees and Medicare benefits led to the AMA withdrawing from future participation in annual enquiries into fees for Medicare benefit purposes. Subsequently, because of undue obstruction by departmental representatives on the Medicare Benefits Schedule Revision Committee, the AMA also withdrew its participation from that body. Fees were again in the news in late 1987 when the Chairman of the Government’s Price Watch Committee launched an outrageous attack on alleged overcharging by doctors, an attack which lasted several months. In the end, the AMA succeeded in protecting the interests of doctors and patients.

Quality assurance was in its relative infancy in Australia, although the AMA was in the forefront of international activity. The AMA/ACHS Peer Review Resource Centre was established in 1979 with seeding funding from the government. When that funding ceased in 1986, so did the Resource Centre. The AMA took over responsibility for the further expansion and consolidation of clinical review activity, while the Australian Council on Healthcare (or Hospital as it was then) Standards was responsible for continuing education in peer review. Looking back, one recalls the difficulties and intense resistance generated by the introduction of the concept. Yet, against strong initial opposition, it is now a principle embraced by all professions and disciplines. Diagnosis-related groups were introduced in 1986 as the basis for hospital funding.

I wish to pay tribute to the members of my Executive, Federal Council and members of the Secretariat. Their support, loyalty and advice were essential in carrying out my duties. I thank them sincerely.

Dr Trevor G Pickering: AMA President 1985-88

AMA President Breakouts: Change in the Air

On assumption of the Presidency in May 1982, I was deeply conscious of the new Labor Government’s health plans, to be called Medicare, and the ongoing continuum of problems dating back to the introduction of Medibank which had, in 1973, been fiercely opposed by the AMA. Then it had been difficult for the AMA to engage in meaningful discussions with the Labor Government because of the stated non-negotiatability of many of its plans. On this occasion, the AMA resolved to minimise, and indeed remove, government interference in the practice of medicine. Much was achieved but the greater control of medicine remained the Government’s frequently stated objective.

At a broader level, the Government unsuccessfully sought to control the incomes of all the professions by persuading professional bodies to submit their fees for determination by the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. The AMA was heavily involved in this issue through the Australian Council of Professions – unity is strength, a lesson that individual doctors and groups of doctors tend to forget.

The major activity in 1984 was the fight against the onerous provisions of Section 17 of the Health Insurance Act introduced with Medicare. Section 17 gave the Minister the power to impose any controls he chose on the private practice of medicine in public hospitals, including control of fees. Following many negotiations, we received the report of the Penington Inquiry, which showed that the Government had acted in haste on wrong information when it provoked Australia’s first doctors’ strike.

While the report was being considered at many meetings, the New South Wales hospitals dispute erupted. I was asked by the NSW Branch and the Senior Royal Clinical Colleges to intervene. This led onto a period of frenetic activity, which was to last almost to the end of my Presidency in 1985. The peace package announced in early April 1985 addressed many of the problems arising from the dispute. Most commentators saw it as a major victory for the AMA and for the profession. The major concession was undoubtedly the complete retraction by the Federal Government of the amendments to Section 17 of the Health Insurance Act. Other concessions included choice of modified fee-for-service for visiting doctors at metropolitan district and country hospitals, withdrawal of the Commonwealth from regulation of private hospitals, and an improved private hospital insurance package.

Some dissident members of the Association, whose real agenda seemed to be the fall of the Hawke Labor Government, called for an extraordinary general meeting to consider a motion of no confidence in me. It was held in Canberra on 11 May. The motion was defeated on proxy votes by 7232 votes to 1196 – 86 per cent of the votes were cast in my favour. After the meeting, I issued the following statement: Today’s vote not only vindicates me personally but also preserves the honour, stability and credibility of the Association. This is of great importance to all doctors. The AMA is and will continue to be the only effective representative body of the medical profession. My ongoing thanks remain for the support of the members of Federal Council and our excellent staff, led by the Secretary General, Dr George Repin.

As Chairman of the Constitution Committee of Federal Council, I had long recognised the need for the AMA to adapt its structure and function to meet demands placed upon it. Fortunately, constitutional change occurred under my successor as President, Dr Trevor Pickering, but not without vigorous opposition. This has allowed the Association to continue to represent the profession as a whole in an effective manner. The profession needs an effective unified national body. Looking at the profession today, I see increasing bureaucracy and unnecessary red tape. As a true profession, we seem in danger of losing our sustaining ideals and of becoming a series of fragmented disciplines that are prisoners of the technology that increasingly separates us.We need to re-commit to ethics and quality of service. Remember the words of a former editor of The Lancet, Sir Theodore Fox: “the human race does not need a doctor, whereas human beings do”.

I greatly enjoyed my term as President despite the stresses and strains, especially on my family and patients.

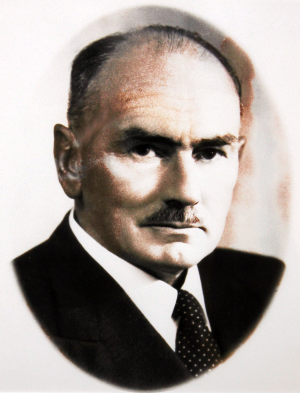

Dr Lindsay Thompson: AMA President 1982-85