Hospital system shows cracks under weight of demand and under-funding

A 28-year slide in hospital beds relative to Australia’s ageing population and one in three people waiting more than the recommended 30 minutes to commence treatment for urgent Emergency Department (ED) care highlights the pressing need for a recovery plan for Australia’s failing public hospital system.

A 28-year slide in hospital beds relative to Australia’s ageing population and one in three people waiting more than the recommended 30 minutes to commence treatment for urgent Emergency Department (ED) care highlights the pressing need for a recovery plan for Australia’s failing public hospital system.

The Australian Medical Association (AMA) 2022 Public Hospital Report Card shows that since 2008 Australia has lost six public hospital beds for every 1000 people aged over 65 years.

The most recent data from 2019-20, shows the ratio of total hospital beds for every 1000 people aged 65 and over dropped to 14.9 – a decrease of one bed from the previous year at 15.9.

Public hospital beds per 1000 people aged 65 years is a key measure of public hospital capacity.

AMA President Dr Omar Khorshid said this ratio had been on a downward trend for 28 years and, along with funding shortfalls, contributes to public hospital over-crowding and long waiting lists for emergency and elective surgery treatments.

“Thirty years ago we had more than 30 beds in our public hospitals per 1000 people over the age of 65, we now have fewer than 15 and our population is ageing,” Dr Khorshid said.

“We expect that by 2035 more than one million will be older than 85 – almost double of what it is today. 2035 is not very far away and if we want to save our public hospital system we must act now.

“Our public hospital capacity must be expanded to meet the demands of a population that is increasing in size, age and suffering from multiple chronic health issues. This needs to be backed by greater investment in primary care, giving GPs the support they desperately need to keep people out of hospital.”

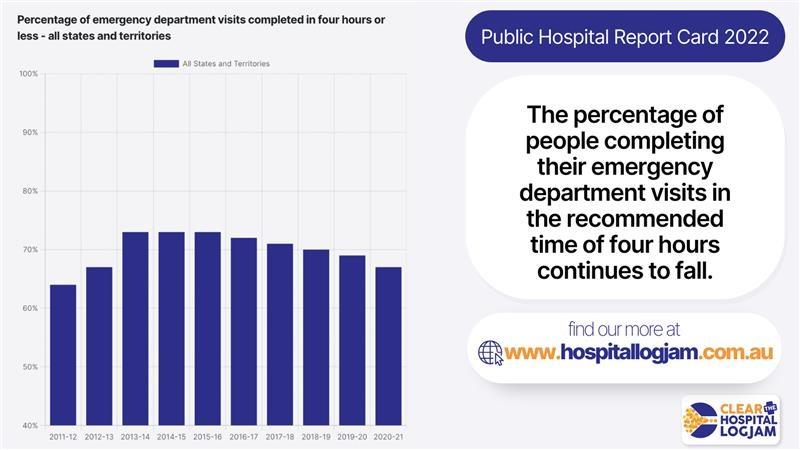

Dr Khorshid said the 2022 Public Hospital Report Card clearly demonstrated the growing pressure on emergency departments.

More than one in three people waited longer than the clinically-recommended 30 minutes to receive urgent care. In 2020-21, 63 per cent of ED patients, down from 67 per cent, were seen within the recommended period.

“One in three people who present to an ED will wait longer than four hours to be either discharged or admitted. This is why we see increased ramping of ambulances in front of our hospitals and why patients are suffering unnecessarily.”

Dr Khorshid said the situation was even worse when it comes to elective surgery.

“As this Public Hospital Report Card shows, during 2020-21 one in three patients waited longer than the clinically indicated 90 days for Category 2 elective surgery, which includes conditions such as heart valve replacements or craniotomy for an unruptured brain aneurysm.

“The decline in performance is even worse with Category 3 elective surgery wait times continuing to blow out. One in five patients (20.6 per cent) waited over a year for hip replacement surgery in 2020-21. And one in three (31.7 per cent) waited longer than the clinically indicated 365 days for knee replacement. That’s an increase of almost three times compared to the year before, when only one in ten patients (11.4 per cent) waited over a year,” he said.

Dr Khorshid said the picture worsened further when the so-called “hidden waiting list” was considered. This was the time patients had to wait between referral from their GP to seeing an out-patient specialist to assess their need for surgery.

Although there is no consistent national reporting methodology on hidden waiting lists some states were reporting their own figures.

In Tasmania currently, there are more than 59,000 patients waiting to see a specialist in a public health system, including patients waiting close to 800 days to see a neurosurgeon with an urgent referral.

Dr Khorshid said health policy decision makers needed to understand and recognise that costs associated with inadequate prevention and delayed elective surgeries go beyond the health system.

“Every delayed surgery has an impact, leading to loss of quality of life and further deterioration of health. Delaying a minor surgical intervention to improve the hearing of a child may mean they miss crucial time for physical and mental development.

“This is likely to incur much larger costs throughout their life than the cost of surgery. All these costs are covered by taxpayers and should not be seen as separate. We need all levels of government to stop shifting the costs and work together to solve these problems.

“Australia urgently needs a recovery plan for its public hospital system. We need appropriate funding to clear the backlog of elective surgeries, and to build enough capacity to meet the growing needs of the community.

“We have the solution. Our ‘Clear the hospital logjam’ campaign calls for partnership funding for more beds and staff to meet future community demand, with no caps and a more equitable share of funding between states, territories and the federal government.

“We also need to end the blame game that often stifles innovation and to agree on a range of measures to support general practice to deliver the type of care that will help keep people out of hospital and enjoy a better quality of life.

“It’s time politicians recognised the underlying cause of the yearly decline in public hospital performance is the failed hospital funding agreement.

“Which government will be able to say they reversed the decades-long decline in our public hospitals’ performance? Wouldn’t that be a remarkable achievement?

“We’ve talked about ‘flattening the curve' for the last two years with COVID, but it’s high time we ‘bent the curve upwards’ on our hospital capacity and improving ED treatment times and elective surgery,” Dr Khorshid said.

The AMA’s Clear the Hospital Logjam campaign is aimed at securing a new funding agreement to improve hospital performance, expand capacity, and address avoidable admissions. This includes moving to a more equitable 50-50 funding share between the Commonwealth and states and territories, and removing the 6.5 per cent funding cap that constrains the ability of hospitals to meet community demand.